Germany's Green Card would probably have gone down as a footnote in the history of the country's migration debate had it not been so misjudged. It was introduced 15 years ago, on August 1, 2000, only a few months after Social Democrat Chancellor Gerhard Schröder had announced the measure at the international computer trade fair in Hanover, much to everyone's surprise. The IT industry wanted to hire skilled professionals quickly and with a minimum of red tape. Back then, there had been an estimated shortage of 75,000 skilled workers in information technology. Russians, Bulgarians, Indians and people from all over the world were expected to stream into Germany.

The Green Card did indeed make it possible for non-EU citizens to quickly obtain a work and residence permit, sometimes even within a week. But under what conditions? The professionals were allowed to stay a maximum of three years, with an option to extend for another two. They had to have a university degree in IT or provide proof of an expected annual salary of 50,000 euros. Their family members were not immediately allowed to work in Germany, and Green Card holders were also not allowed to be self-employed. Only 18,000 IT professionals took the opportunity to go to Germany, meaning that the government's limit of 20,000 Green Cards had not even been reached. In 2005, the Green Card regulation was replaced by the new immigration act. Looks like things didn't work out, right?

Fifteen years ago, the German public seemed distraught, almost frightened, about Schröder's intentions. Many opposition politicians, but also trade unionists and even some Social Democrats, had to get used to the idea that Germany's shortage of skilled workers - and not only in the IT sector - would not be solved within the country's borders. It was difficult for people to accept this news. "Children - not Indians," said people who still had hopes of filling positions with young Germans. Anxieties were expressed over foreign infiltration and wage dumping, and countered by arguments for the idealistic side of labor migration and a welcoming culture, and Germany finally began a long overdue debate on immigration. The country did away with the old adage of "not being a nation of immigrants." It was a reality check, courtesy of the Green Card.

Germans can use the Green Card example to understand why their country is far from a dream destination for highly qualified professionals from around the world, even as the demand for these workers continues to grow. The Green Card has shown that too much red tape is simply counterproductive if the country wants to attract specialists from around the world to its job market. Even the requirements for the Blue Card, which has been opening the door to the European labor market to highly skilled workers since 2012, must be reconsidered; for instance, not every specialist has a university degree.

With regard to the Green Card, Germans should stop and ask themselves if they have managed to create a credible welcoming culture in the past 15 years. All things considered, foreign professionals will surely ask themselves if they can really live and work in Germany. I fear that Germany's image in the rest of the world has been tainted with images of burning refugee homes. Who would dream of working in a place like that?

DW

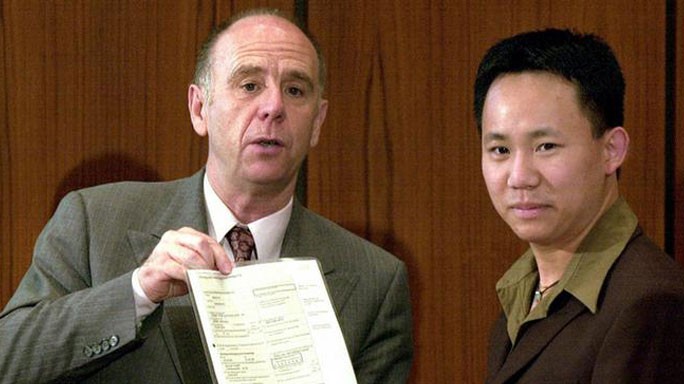

Picture: DPA